An Ensemble of Voices from the Homeland: A Review of Jared Lemus’s Guatemalan Rhapsody

In his debut short story collection, Guatemalan Rhapsody, Jared Lemus assembles dynamic slice-of-life stories about men and boys living in Guatemala and its diaspora, a perspective that enriches the growing canon of Latinx lit. With eight stories set in Guatemala and four in the United States, readers accompany unassuming characters as they scrape by in their personal lives and at service-based jobs, such as driver, janitor, cook, builder, hotel worker, and laundryman. The weight of fractured lives and financial strain bears down on these protagonists, who typically respond with some measure of machismo.

The opening story, “Ofrendas,” presents an operatic scene of sacrificial self-immolation in the Guatemalan Highlands at a temple dedicated to San Simón, a religious icon of Indigenous Mayan and colonial Spanish origins. Distraught petitioners seek favor from the revered deity, who is both trickster and protector, in exchange for offerings such as cigarettes, aguardiente, sugar, chocolate, and money. As the first and most lyrical piece in the collection, “Ofrendas” sets a metaphorical backdrop of thematic juxtapositions–such as the ancient and modern, desire and addiction, anger and sorrow, guilt and repentance–that trouble the characters throughout the book’s pages.

Many of the stories feature first-person speakers who relate their outward experiences more openly than their inner lives, a narrative choice that mirrors their aversion to vulnerability. Readers must decipher meaning from between the lines or the striking visual compositions. We are not granted epiphanies, only biting wit, self-chastisement, and emotional deflection. Women, however, are the exception. Though relegated to supporting characters, the women in Guatemalan Rhapsody supply both truth and compassion, able to articulate what the men in these stories are unwilling to admit.

Lemus also gives readers a new way to understand non-English dialogue in stories written in English by utilizing Spanish-style punctuation. Guatemalans naturally converse in Spanish and various Indigenous languages, but Lemus writes all dialogue in English while signaling to the reader that the conversation is happening in another language–such as opening and closing a statement with question marks or exclamation points. ¡Like this! The effect is a smooth and delightful linguistic ride that immerses the reader more deeply into the characters’ lives.

A push-and-pull energy drives rocky relationships between the fathers, sons, friends, and siblings in Guatemalan Rhapsody. In “Dark Road with Diesel Stains,” a drug-hungry trucker takes his son, whom he rarely sees and refers to coldly as “the kid,” on a long-haul delivery. One evening, the trucker remembers a family trip to Guatemala when his father left him alone in the jungle overnight to initiate manhood. In a desperate attempt to replicate the lesson with his own son, the speaker reasons that “[…] maybe he will grow up stronger than me.” This lone-wolf character howls across the dark highway, beckoning his frightened son to find his way back to him. The father’s yearning to connect but failure to do so is a heartbreaker Lemus revisits throughout this collection.

Two stories center on brotherhood among orphaned siblings in Guatemala. In “Saint Dismas,” four young brothers survive as roaming thieves after their town is overrun by gangs and their parents are killed. The eldest remains angry and untrusting, making decisions for the group to keep them alive but inadvertently driving an emotional wedge between himself and his brother, the speaker. In “Hotel of the Gods,” adult brothers undertake renovations on a remote hotel–now a rundown incarnation of their father’s dream. Yet, the mix of one’s addiction and the other’s apathy leaves them with nothing but ashes where their inheritance once stood. In both stories, the brothers handle daily stressors by issuing orders, exchanging insults, or one-upping each other, yet not without some measure of care.

Lemus’s characters exist in the aftermath of unnamed ruptures. In the United States, that damage might be broken homes. Seemingly unanchored in time and space, these men live in unnamed cities, rent cheap apartments, are unhoused, or work on the road. We learn their parents live in Guatemala, so friends and coworkers become their closest ties. In “Whistle While You Work,” Santorío, a university janitor tells a coworker about his parents’ deportation and his goal of earning a GED. He then confesses to the reader: “I didn’t mention that I was actually only two years old when my parents left me behind with my aunt, and that I’d dropped out to help her pay the bills […] staying on even after she too moved back home […].” Similarly, Fernando in “Heart Sleeves” dreams of one day owning a tattoo shop if, he states, “[…] I ever got out of my own way.” Yet, not everything is doom and gloom. Lemus arms these characters with a playfulness and curiosity that reflect their brand of survival while navigating young adulthood on unsure footing.

The Guatemalan-based stories, in contrast, hint at socio-economic ruptures. Unlike the nameless U.S. locations, specific Guatemalan cities and towns are mentioned, even named with tongue-in-cheek humor, such as the town of Quenotepegue (i.e. don’t let it/them hit you) in “So Long to the Rearview,” which first appeared in Story Issue 14 (Summer 2022). In Guatemala, the characters have deep connections to the land. Take Sergio, the elderly protagonist in “Carías,” who has lived his entire life a short walk from a waterfall and swimming hole he unofficially oversees. When a menacing visitor repeatedly vandalizes it, Sergio risks his life to protect the hallowed site where his brother died in a childhood accident. In “Fight Sounds,” the cocky lead, Antonio, feigns dominance over his village and love interest when an American film crew rolls in and shakes up the status quo. Although these characters struggle within the grip of poverty, we sense the spirit of home, a place of beauty and heartache.

Arriving at the critical moment of tumultuous geopolitics, Guatemalan Rhapsody amplifies an ensemble of fictional voices from a Central American country whose diaspora is underrepresented in contemporary American literature. Lemus asks readers to consider the unvarnished life experiences of seemingly ordinary men and boys surviving extraordinary generational challenges, in both their homeland and abroad. Whether these stories harmonize with or clash against the readers’ senses, they offer a novel, energizing reading experience attuned to the realities of the Americas.

A Conversation with Jared Lemus

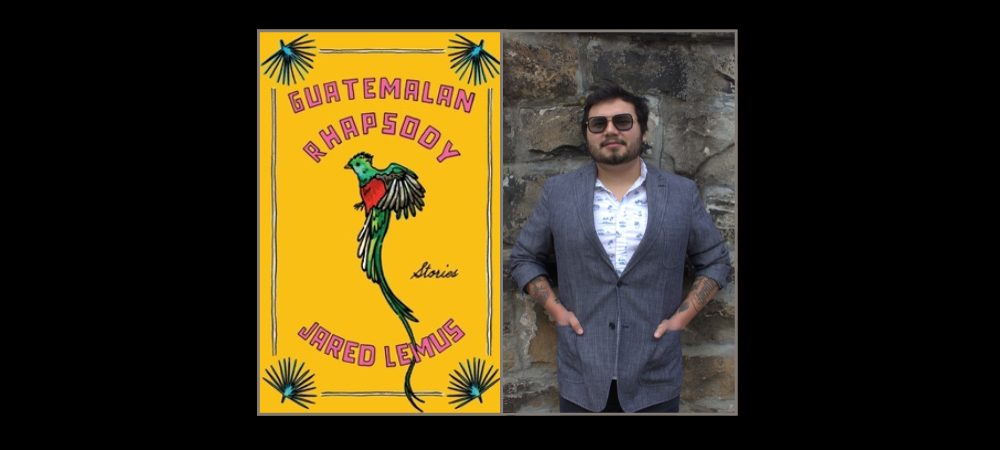

Jared Lemus is the author of two works of fiction forthcoming with Ecco-HarperCollins. His story collection, Guatemalan Rhapsody, was published on March 4, 2025—his novel’s not far behind. Lemus’s work has appeared in The Atlantic, Story, The Pinch, and The Kenyon Review, among others. He holds an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh and is currently the Kenan Visiting Writer at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Fiction Editor Sela Chávez connected with Jared Lemus via email to discuss the craft and inspiration behind the stories included in Guatemalan Rhapsody.

INTERVIEWER

When I read the book’s title, Guatemalan Rhapsody, my mind leaped to “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen, a multi-movement song with ballad, opera, and hard rock tones. In music, rhapsody welcomes improvisation and shifts in mood. Can you tell us why you chose this title to represent the twelve short stories included in this collection?

JARED LEMUS

That’s exactly what I had in mind with the title—a nod to the composition and movement of “Bohemian Rhapsody.” This is why the order of these stories is so intentional. Like following “So Long to the Rearview”—a fast-paced story that echoes the life of our main character and all its dangers—with “Whistle While You Work”—a love story of sorts where stakes are still high (the loss of means) but with a calmer energy to give the reader a chance to catch their breath before continuing to “Saint Dismas” where we start to rev up again with the life of four teenage highway robbers. It’s not just the literal stakes that drive the story’s structure; it’s also the vibes. Running a hotel with a ton of tourists and losing control in “Hotel of the Gods” sounds stressful (because it is!), but the brothers in the story are also funny. The calm/complacent one balances out the somewhat manic one. All the stories work together to create one cohesive collection with each story bringing its own signature style and voice to contribute to the whole. But at the end of the day, the title is an acknowledgment—this is a song to, for, and about the people of Guatemala and its diaspora.

INTERVIEWER

Many of the stories center on men caught in the daily hustle of making a living, mostly at low-wage jobs. They struggle with familial and romantic relationships, addiction, and guilt. All are distinctly drawn characters, yet they share a familiar air of Latinx machismo, often short-fused and sharp-tongued. How do cultural and social norms sway the men and boys who populate your stories?

LEMUS

That’s one of the main things I wanted to address in my stories. I come from an upbringing with a father who very much embodied all the machismo stereotypes men are supposed to follow. I was expected to do the same but, much to my father’s chagrin, couldn’t and didn’t. It wasn’t uncommon to hear him say to my mother, “Looks like you got the girl you always wanted,” when referring to me and my proclivities. I liked music instead of karate, books and not sports, theater (“Kill me now, what an embarrassment!”) instead of hunting. I wore girl jeans, had long hair, and put on eyeliner and stage makeup (“for God’s sake!”). In short, I was a disappointment. But he failed to notice his relationship with me suffered because of these differing points of view and outlooks on the world and its people, although that doesn’t matter much to someone focused on dominance and control. Because of this, a lot of my characters inhabit these traits without realizing what they’re ruining. The best example of this is in “Heart Sleeves.” These young men love each other but are too afraid to admit it to themselves or one another. They play up these hyper-masculine roles to avoid talking about how much they care, causing themselves and those around them so much unnecessary trouble that could have been avoided had they just admitted love existed between them. It’s in the same vein as the film “Y tu mamá también,” minus the sexual attraction. “Heart Sleeves” is about wearing tattoos (sleeves) on their arms but not their hearts on their sleeves. These characters risk relationships, livelihoods, even lives—theirs and others—to avoid appearing weak, to avoid admitting to another man, even their own child, that they love him.

INTERVIEWER

The eight stories set in Guatemala overflow with regional details, both concrete and conceptual—think machetes, eloteros’ bells, thick jungles, crumbling churches, mountainsides, and waterfalls on one end, and poverty, food scarcity, violence, and Indigenous roots on the other. A Publisher’s Weekly article states that as a child you moved back and forth between the U.S. and Guatemala. In what ways have those experiences surfaced and evolved in your creative work?

LEMUS

I made my first trip to Guatemala when I was less than a year old. I have no memory of this but imagine myself wrapped in a bundle, making my week-long journey from Queens, New York, where I was born. After this, we visited every couple of years. My parents were homesick but also couldn’t quite convince themselves to settle back in Guatemala. We lived in a trailer park here while my parents saved enough money to buy a house back in the country they considered home. We spent three-quarters of the year in the U.S. and one-quarter in Guatemala, eventually buying a house there. It seemed like we were moving back.

Less than a year into our stay in Guatemala City, my cousin had a falling out with his gang. They shot up the house while we were inside. I was ten years old and remember bullets flying through windows, shattering picture frames, while bits of plaster from the walls fell around us. We stayed there long enough to figure out how we were going to move back to the U.S. Afterwards, we continued to visit but never more than 2—3 months at a time and mostly outside the capital city. We stayed with my paternal grandfather, in a place in the mountainous highlands with no electricity, running water, or indoor toilet. We slept in hammocks in a room divided by a curtain to separate the children from the adults. We followed my grandfather into the jungle to chop down fruits and walked down to the stone mill to grind corn and collect water in giant pails to bring back to the house for showers. We visited the lowlands to say goodbye to my grandmother’s abusive ex-husband on his deathbed. Of course, as a child, I wasn’t paying attention to much other than how much my feet hurt from all the walking or not spilling all the water from one pail while my cousins balanced one in each hand and one atop their heads.

I have all these memories, but they’re viewed through the lens of my childhood self who had no idea about Guatemala or its history. Because of this, I try to return to Guatemala every 2—3 years, one month each time, to spend time re-seeing the country through more knowledgeable eyes. It’s no longer “my house got shot up because my cousin was in a gang”—it’s now the history of violence in Guatemala. It’s not “my feet hurt from all this walking”—it’s “this is what people must do to survive another day,” and so on. Sometimes the images and experiences from my childhood show up in the stories—be it an uncle I saw fall drunk from a horse or watching my cousins set off fireworks in the capital. Other times, it’s from my visits as an adult—the chicken buses I’ve taken where I take up adult-sized space now instead of child-sized space or the three teenagers who tried to stop my car along the highway to take my valuables. But the fact remains, this country has more stories than I will ever be able to capture, but I will do my best to continue to tell as many of them as I can.

INTERVIEWER

Your sentence mechanics are distinct. All dialogue is written in English; but, in most cases, the reader understands these characters are speaking in Spanish (or an Indigenous language), which is signaled by the punctuation. I find this refreshing. Could you tell us how you came to your punctuation-bending style of moving between languages in your work?

LEMUS

Absolutely! I arrived there by reading other Latine writers. In most of those English-language books, the Spanish is italicized, which bothers me. No shade at all. It’s just that it calls attention to this “otherness” in the text. And I know other authors who don’t italicize for that specific reason. But I wondered what the next step was. If one is an acknowledgment of “Hey, this is different from all the other text you’ve read so far” and the other is “I won’t acknowledge this is different for your convenience,” then what is the “You’re the outsider here, not me”? In my head, that was the Spanish punctuation in dialogue, as well as the italicization of words spoken in English. I felt this when I started elementary school in the U.S., where I was an outsider listening to other kids and teachers have conversations in which I was simply the observer. It’s a reminder that these characters are living their lives, speaking Spanish to one another, and the reader is looking in on their truths. They’re not speaking English just because someone else is there. It’s the same way I felt a few years ago while staying in a village in Guatemala made up of mostly Indigenous peoples. They spoke K’iche’, and I was once again left out. One day I hope to learn and be fluent in K’iche’ just like my grandmother. Anyway, all of this is to say that I’m always in the in-between, even though I belong to K’iche’ and Spanish and now English. It’s weird to feel left out, even when I belong. I don’t want to isolate, but I do hope the non-Spanish-speaking reader feels a bit of this as well.

INTERVIEWER

Most of the stories in Guatemalan Rhapsody conclude with an image that reverberates. The opening story, “Ofrendas,” does so with a close-up of a boy’s hand, a ceremonial egg, and the licking flames of a sacrificial fire, while the final story, “A Cleansing,” offers a wide shot of a man and girl sitting outside under heavy storm clouds, surrounded by clean white sheets. These final scenes capture themes of pursuing absolution or self-forgiveness. Can you talk about how these two stories work as bookends supporting the collection?

LEMUS

Thank you so much for pointing this out. I’m a huge art and music nerd, specifically of paintings and songs I’ve never heard before. Every time I travel somewhere new, be it a state or country, I have two goals (not counting how to eat as much local food as I can). They are to visit every museum and find as many live music shows as possible. To me, the story is like a song or a piece of art—each sentence is a brushstroke or line of a verse, each paragraph a layer of paint or a chorus—and it’s only when I reach the end or view the painting as a whole that I see and feel the full effect of what has been created. This is what I try to do with my stories. It’s rhapsodic movement from scene to scene, each building a piece of the full image, which also remains a mystery to me until I reach that last sentence and step back to look at it.

Anyway, now that I’m done nerding out, let me reply with more concrete details. The stories bookending the collection hold two “opposing” images. The first opens with fire and ends the same way while the closing story ends with a thunderstorm washing the characters clean of their sins and misdoings. To me, this is a biblical allusion in reverse—“I baptize you with water, but after me comes one who is more powerful than I. […] He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.”—Matthew 3:11. I initially started the collection with “A Cleansing” and ended it with “Ofrendas” because this is the way one must approach the Mayan gods when asking for something. First, you cleanse your soul, then you may approach the fire to make your request. The reason I chose to do this in reverse is because each story in the collection asks its main character to step into the fire full of his sins but promises a cleansing or baptism of water at the end. I’m asking my characters to trust me with their stories. Even if they end up worse off than they were in the beginning, it feels like a confession—in the literal Catholic sense, “forgive me, for I have sinned”—because regardless of what comes after, they have unburdened themselves of that story.

INTERVIEWER

What’s a story from an author of any time or place that is a secret lit crush? What about it enchants you?

LEMUS

I feel like I talk about Adam Johnson more than I ever should. He’s going to start thinking I’m stalking him. But honestly, I just love his writing. Every one of his short stories in the collection Fortune Smiles is a banger. If I had to choose one, it would be the title story, which closes the collection. There are these two guys who have fled Pyongyang for Seoul for obvious reasons. They sell fake lottery tickets to make extra money. It’s an idea I wish I’d thought of myself, but of all the vices my characters possess, not one of them is a gambling addict. But what really sticks with me in that story is the longing for people and things left behind, and Johnson uses that as fuel for propelling the story forward. Not to mention, he writes like he’s receiving radio signals from some other faraway godly entity.

INTERVIEWER

In a Kenyon Review essay, you discuss how your parents tell truths and lies when relating the origin story of their marriage and your family. It’s a funny, bittersweet piece that leads one to consider how and why we twist facts to control our personal narratives. As the United States faces its own identity crisis, any thoughts you’d like to share on the power of rewriting history or even on myth-making as we move deeper into 2025?

LEMUS

Liars fall into two main categories: those who know the truth and purposefully manipulate it and those who don’t know the truth and therefore don’t know they’re lying. Unfortunately, it currently feels like myth-making is serving the liars. The idea that other countries are “sending their worst people,” “criminals,” and people from “insane asylums,” fuels so much xenophobia and hate, which makes people back these mass deportations and detainment (concentration) camps. We have a president who is painting himself a vessel from God, which seems unfathomable given all the biblical warnings about false prophets, but I digress. The point is people believe him or pretend to. What’s the quote? Repeat a lie often enough and it’ll become the truth? Guess who that’s attributed to? Nevertheless, this seems to be the approach to myth-making right now: self-aggrandizement. What we need is truth-making.

INTERVIEWER

When American characters appear in the stories set in Guatemala, the air thickens with entitlement. At best, they clumsily interact with the locals, as does the Hollywood film crew in “Fight Sounds.” At worst, they terrorize locals, as in “Caídas,” where a young American tourist strategically vandalizes a waterfall and verbally accosts its elderly caretaker. The United States’ historical role in upending Guatemala and exacerbating its poverty and corruption remains unspoken in Guatemalan Rhapsody, yet the specter of that disruption haunts. What’s something most people might not know about the Guatemalan-U.S. relationship that would enrich their reading of your work?

LEMUS

As you just mentioned, the history of Guatemala goes unspoken, at least on the page; but it is definitely there, as you have beautifully put it, as a specter of that disruption that haunts. The main reason I didn’t state it explicitly is that it was more painful to read and write than I anticipated. According to my 23&Me, my lineage avoided Spanish DNA for hundreds of years, with my last full-blooded Indigenous relative being born in the early to mid-1900s—presumably, my grandmother. So, now we have part of my ancestors committing mass murder and genocide against another part of my ancestors for 36 years (from 1960—1996). How does one approach something like this when writing fiction? Do I tell it from the point of view of one of the soldiers committing these atrocities (possibly one of my grandparents), from the point of view of an Indigenous person (possibly another grandparent) who must witness this, or from a guerilla fighter (another possible ancestor)? Trying to tell these stories took an emotional and mental toll on me. So much misery and sadness and unnecessary violence. And that’s one thing I knew I didn’t want to write—gratuitous violence. I didn’t want this to be a war movie or a Tarantino film. So, I let go of those stories for the time being and decided to focus on the aftermath of one of Guatemala’s most violent periods. What we get instead are the stories of the people who remained. Some leave; others don’t have that option.

But, to answer the question, what some people might not know that would definitely help enrich their reading experience is that Ronald Reagan and his policies brought Guatemala to its knees, that we had a U.S.-backed genocide referred to as the “Guatemalan Civil War” from 1960—1996. The military massacred, raped, and tortured almost the entire Indigenous population under the guise of killing communists—a.k.a. those opposed to the oppressive U.S.-endorsed government put in place to make the U.S. richer while exploiting Guatemala and its people through entities like the United Fruit Company. Guatemala never recovered, leading to a government run by corrupt politicians and scared politicians—the difference being one set threatened by the gangs that sprang up and took control when the country was in flux. The other being paid by those gangs to keep them in control. As we just witnessed another genocide, this time in Palestine, with the U.S. backing and arming the oppressor, it seems history will repeat itself unless we tell its complete history more widely.

INTERVIEWER

At the beginning of Vanessa Angélica Villarreal’s 2024 book MAGICAL/REALISM: Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy, and Borders she offers a graphic titled “The Migrant’s Journey” that subverts the myth of the hero’s journey. Even though the short stories in Guatemalan Rhapsody might not deal head-on with migration, undocumented people, family separation, and first-gen struggles, these themes have their mark on your characters. What draws you to write about Guatemalans or their descendants living in the U.S., or what Villarreal terms “The World That Matters” (as opposed to their “Shithole Country” of origin)? What do you hope your work captures about how these characters navigate displacement and in-betweenness in pursuit of a better life?

LEMUS

You’ve touched on something really important to me here. Similar to Villarreal’s graphic, when one typically thinks of the “migrant’s journey,” the story’s resolution or happy ending is a “successful” crossing of the border (this can, of course, be both literal and/or in the sense of assimilation). Yes, there were trials and tribulations along the way; but look, you made it—congratulations. That’s it. Fade to black. Roll the credits. Is this the extent of the White American’s understanding of these stories? I wonder if they think we ascend straight to heaven right after we “successfully cross the border”.

Almost every migrant I’ve ever known, my parents included, wish they were home. They’re only here because of what the U.S. has done to their home countries. This is something I try to address in the collection. Four out of the twelve stories take place in the U.S., and every one of those has characters (much like myself) with parents who immigrated to the U.S. or sent their children to the U.S. in hopes they might have a better life. But that’s only the beginning of their story. Some are homesick, some try drowning or numbing their sadness with drugs. They have all the struggles of U.S.-born citizens with the added baggage of language barriers, cultural barriers, racism, xenophobia, the lack of generational wealth, and incorrect documentation or certification for jobs they could have easily gotten in their home country—just to name a few things. This is why I have stories like “Whistle While You Work” where, sure, this character lives in the U.S. (a success story already!), but his entire family has been deported back to Guatemala, leaving him to pay for his college degree so he can hopefully get a better job. So, yes, my stories don’t deal directly with migration, undocumented people, first-gen characters, and so on, but rather with the aftermath of these things, challenging what some consider the end of the story and turning it into the beginning.

INTERVIEWER

What would you like to share with us about your upcoming novel? How does it relate to or depart from Guatemalan Rhapsody?

LEMUS

Let me start by saying thank you for engaging with my work so thoroughly. I feel seen and heard, so thank you. My upcoming novel is, in many ways, also a rhapsodic work of fiction. It’s polyphonic and centers around the characters in the fictional town of Huecotenango, Guatemala—a place where you end up when you have exhausted all other options and have nowhere else to go. The biggest departure from the collection is the novel includes and centers on more female voices. I don’t think it gives too much away to say I’m also dabbling in what I consider the Latine tradition of Magical Realistic storytelling.

In many ways, the novel is an extension of the collection. They’re in conversation with one another on multiple levels, not least of which is the centralization of Guatemala, its history, and people. As I mentioned earlier, this is a country scarred by the presence of the United States and its army, a country that has never quite recovered from U.S.-involved government elections, U.S.-aided destruction, and U.S.-backed genocide. One thing that will remain the same in my novel and all my future work is that this is a work of literature—a song I won’t stop singing at the top of my lungs—that I hope will uplift Guatemala and its people.